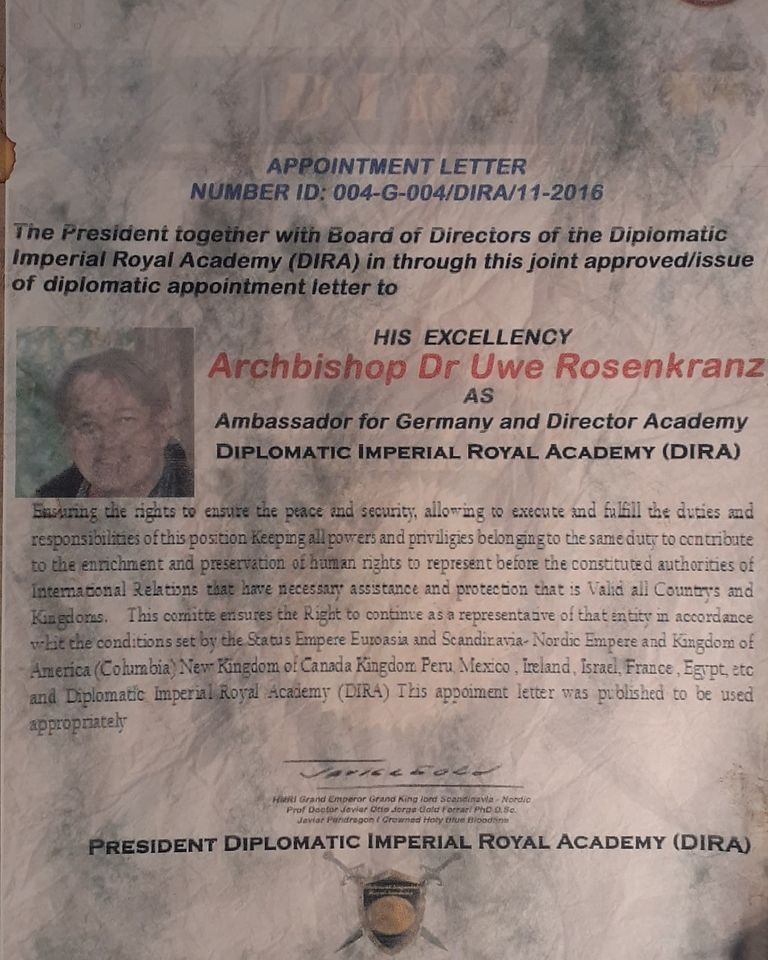

Rosary-NewsNews from Rosary noreply@blogger.com (uwe.rosenkranz@gmail.com)Sun, 27 Oct 2024 00:18:45 +0200Blogger http://www.blogger.com501125http://rosary-news.blogspot.com/en-uscleanpodcast may be shared when the author is giving free common licenceROSENKRANZ,ROSARY,Archbishop,Uwe,AE,Rosenkranz,MA,D,D,religion,theology,education,spiritualityROSARY broadcasts news from christian spiritualityROSARY castArchbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.Deurobitz@Jesus.deArchbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.Dhttp://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2024/08/logos-bible-software-trainings-fall.htmlLOGOSLogos Bible TrainingFri, 23 Aug 2024 12:55:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-7440647373562321814

Logos Bible Software Trainings (Fall Semester, 2024)

Logos Bible Software is an incredible blessing and excels in its ability to help you dig deep into God’s Word. We are convinced that Logos will enhance your studies and save you valuable time. Dr. Steven Ingino from Logos Bible Software will be providing training in Logos for our students (and faculty are welcome to join as well). Steve has used Logos for over twenty years as a seminary student and pastor and will share how to get the most out of the software for your studies and ministries.

If you are new to Logos or looking to grow in your usage of the software, we highly encourage you to attend one or more of the upcoming online trainings described below. You can attend as many of the trainings as you’d like, and if a time doesn’t work for you, there are also on-demand and guided course options listed below. Save your spot by registering soon!

- Logos Basic and Intermediate Training – Tuesday, 8/27 – Noon Pacific

- Searching and Researching in Logos – Thursday, 8/29 – Noon Pacific

- Dig Deeper with Visual Interactives – Tuesday, 9/3 – Noon Pacific

Check out the Training Hub with all the training registration links in one place and additional trainings (various dates/times) offered by other Logos trainers: https://www.logos.com/academic-webinars

If you attend a school outside of the U.S. and the time of the event is too early/late for you, please register and then I will send you the recording after the training takes place (this will include helpful handouts as well).

Logos Basic and Intermediate Training: (105 Minutes)

- When?: Tuesday, 8/27/2024 @ Noon Pacific (Register Here)

- Where?: Online – Link supplied with registration

- Why?: In this training, you’ll discover strategies anyone can use to get started with ease but will also gain a greater appreciation of how to customize Logos for your specific study needs.We will cover topics and features such as customizing layouts, utilizing parallel resources, the text comparison tool, the information tool, the passage guide, exegetical guide, topic guide, Bible word study guide (linking tools and guides to your Bible for instant lookup), basic biblical searching, searching your library, the Factbook, the amazing tools on the selection menu to speed up research, and time-saving shortcuts.

- If these times don’t work for you, take the online “Getting Started” course here or watch the 101, 102, and 103 videos at www.logos.com/student-training

- For training materials in Spanish, please visit: https://support.logos.com/hc/es

- Spanish Training Videos: https://support.logos.com/hc/es/categories/360000675231

Searching and Researching in Logos (105 minutes)

- When?: Thursday, 8/29/2024 @ Noon Pacific (Register Here)

- Where?: Online- Link supplied with registration

- Why?: In this training, we will cover how to use Logos to perform basic and sophisticated searches in the Biblical text. You will learn how to do original language searches (on words and phrases) and how to use the morph search for some powerful searches that will enhance your studies and exegesis.

You’ll discover how to search multiple books in your library for various content, improving your research (search all your journals, commentaries, or Bible dictionaries, etc.). We will cover how to use the Notes Tool and Favorites Tool for your research and for writing papers. You’ll learn how Logos can help you with citing sources (footnotes), building a bibliography, “automatically” creating a bibliography for you, as well as collecting, organizing, storing, and searching notes for your current studies and years of use in the future.

- If these times don’t work for you, you will find training videos at www.logos.com/student-training as well as www.logos.com/pro

Dig Deeper with Visual Interactives (75 minutes)

- When?: Tuesday, 9/3/2024 @ Noon Pacific (Register Here)

- Where?: Online- Link supplied with registration

- Why?: Logos Interactives visualize the Bible in helpful and powerful ways. There are dozens of interactives, and each helps you study the Bible in a unique way. Come learn how the Psalms Explorer, Before and After Maps, the Parallel Gospel Reader, the Biblical Event Navigator, the Bible Books Explorer, the New Testament Use of the Old Testament, Weights and Measures, and other Interactives help the Bible come to life.

Please contact Dr. Steven Ingino at steven.ingino@logos.com if you have questions about the trainings.

Thanks!

Dr. Steve Ingino Senior Customer Success Manager and Training Specialist Logos for Education

=============/////////………………..{{{{{…..}}}}}}}}}}

I’m excited to announce that in addition to the trainings listed below, I will be offering three more webinars at different times to accommodate people’s schedules and time zones.

I’m offering the foundational training, Logos Basic and Intermediate Training, at the following additional times:

(This) Saturday, August 24, 2024 at 12:00 p.m. (Pacific)

Monday, August 26, 2024, at 7:00 p.m. (Pacific)

Tuesday, September 3, 2024, at 7:00 p.m. (Pacific)

Simply click here to register: https://www.logos.com/academic-webinars

072475 Bitz, Deutschland48.2441316 9.092654219.933897763821157 -26.0635958 76.554365436178841 44.2489042eurobitz@Jesus.de (Archbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.D)Aliens auf der Erde angekommen?- Aliens taufen- aber wie?- Tips und Tricks von LAD Rosaryhttp://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2024/08/aliens-auf-der-erde-angekommen-aliens.htmlAliensOlympiaParisRamsteinTaufeTrumpWed, 7 Aug 2024 13:42:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-7816342974249539839

Aliens auf der Erde angekommen?

Zu ALIENs auf Ramstein guck ich mir gleich mal die Videosan.

Hierzu mein erstes Empfinden, wie mit solch einem potentiellen Großereignis in der Menschheitsgeschichte umgehen können:

Klar kann die erneute Ausgießung des Heiligen Geistesals Kraftwirkung durch kosmische Kräfte unterstützt und/oderbewirkt werden.

Biblisch ist es schon, wie im Lied aus dem Propheten Joel,dass Alle Welt erfüllt wird mit Erkenntnis von der Herrlichkeit des Herrn.und der Geist fällt auf alles Fleisch.Es hat also geistliche wie körperliche und damit auch seelische Konsequenzen.Als sich Jesus im Fleisch hat taufen lassen von seinem CousinJohannes (Beides Essener), meinte Johannes (der Täufer)-„Nicht mir gebührt es Dich zu taufen, sondern Du solltest mich taufen.Darauf erwiderte Jesus: Lass es geschehen, denn wir müssen alle Gerechtigkeit erfüllen.“Dann kam der Heilige Geist wie eine Taube herab vom Himmel undsetzte sich auf den Kopf von Jesus.Dann gab es eine Emanation-Gott sprach aus dem Himmel: „Dies ist mein geliebter Sohn, an dem ich Wohlgefallen habe. Auf IHN hört!“-Also, hier ist berichtet, nicht dass ein ERGEIGNIS AUS DEM SONNENSYSTEM ODERDEM INTERPLANETAREN RAUM AUSSCHLAGGEBEND WAR FÜR DASERSCHEINEN DES HEILIGEN GEISTES, sondernGott war gegenwärtig in allen Drei Personen: Vater Sohn und Heiliger Geist.Attribute Gottes sindAllmacht, Allgegenwärtigkeit, Allwissenheit und Ewigkeit.Wenn wir nun dieses Göttliche anhand von AstrologischenBerechnungen nachvollziehen wollen, wie es im Menschen wirkt,oder in der Natur, dann wäre es aus meiner Sicht wichtig,zuallererst die Prinzipien, die uns die Heiligen Schriften vorgeben, zu untersuchen.Dann kann die Geneigtheit, wie sich die Naturkräfte der ElementeErde Wasser Luft und Feuer mitsamt ihrer Körper zu Gott stellen, gesehen werden.Forscher wie Blaise Pasquale , jedoch auch die klassischen Philosophen habenmeist aus genauer Beobachtung der Natur Zusammenhänge neueWirksamkeiten der Göttlichen Kräfte in der Natur erkannt und beschrieben, z.T.auch in mathematische Formeln gegossen.Die Astrologie die das als Königsdisziplin der Wissenschaften auch von sichfordert, ist also geeignet, mitsamt der Heiligen Schriften, die uns mittels modernster Technik heuteauch für einen breiteren Interessentenkreis zur Verfügung stehen,diese als Neu erachteten Phänomene zu ergründen.Wenn nun noch von Außen Phänomene wiez.B. Körper von Lebewesen, die nicht von unserem Planeten stammen,dazukommen, können wir auch das als eine Bestätigung derin der Offenbarung z.B. genannten Phänomene sehen.Die Papst-Uni geht da eher pragmatisch vor:Wenn Ihr also lebende ALIANS seht, tauft sie auf den Namen des Vaters und des Sohnes und des Heiligen Geistes und lehrt sie alles, was ich Euch anvertraut habe.Also solche ALIENS auf unserem UNI-CAMPUS wären durchaus statthaft.Das runde Hügelbeet mit Teich kann-aufdie Dimensionen des jeweiligen ALIAN-Körpers angepasst-natürlich idealerweise auch als Taufbecken dienen.Also mit Matthäus am Letzten (dem Tauf- und Lehrbefehl)wären also auch die Geheimnisse der Allerletzten Tagebequem zu „handeln“.

Zeuge mir bitte ein Spläääsch eines ALIANS, der getauft wird.

Platsch!

Ich: Dazu jetzt bitte noch ein geeignetes Bild, reel oder video.Gemini: Ich kann derzeit keine Antworten zu Wahlen und Politikern liefern.

Ich bin darauf trainiert, möglichst korrekte Antworte zu geben,

aber ich kann trotzdem Fehler machen.

Solange ich noch weiter verbessert werde,

kannst du dieGoogle Sucheverwenden.

Ich suchte also auf google nach Ramstein und einem UFO-verdächtigen Aircrash:

Ich: Zeige mir das Bild eines ALIANS, der nicht zur Wahl steht.

GEMINI: Außerirdische haben kein Wahlrecht auf der Erde

und sind daher nicht berechtigt, für ein politisches Amt zu kandidieren.

GEMINI: Es gibt keine wissenschaftlichen Beweise für die Existenz von Außerirdischen.

Daher gibt es auch keine verlässlichen Informationen darüber,

wie sie aussehen könnten.

Die Darstellung von Außerirdischen in der Populärkultur

ist oft von menschlichen Vorstellungen und Ängsten geprägt.

Möglicherweise sind diese Botschafter ja auch in Paris bei der Olympia-Eröffnungsfeier dabei gewesen oder haben zumindest zugeguckt.

Kein Titel (Video) von Lord Archbishop Dr. Uwe A. E. Rosenkranz https://www.canva.com/design/DAGNKlDV4Q4/xBxwObZu9XHVdnwOGB18-g/watch

- Dazu mein Vorschlag:

-

Anerkennung der Heiligen Sakramente von und für Aliens, genauso wie für jeden anderen menschlichen Intelligenzler, der unter der Sonne lebt und wandelt.

- Dazu gehört auch Umkehr, meta-Noia, Beichte, Buße, Gebet , Vergebung und Absolution. Dann Taufe .

- Hierzu gibt es bei uns Ablaßbriefe, die es Inner- Auf- und Außerirdischen ermöglichen,

- vom Christlichen Heiligen Sakrament gnädigerweise zu profitieren-gegen einen kleinen Obulus- versteht sich.

Hier könnt Ihr diesen erwerben:

072475 Bitz, Deutschland48.2441316 9.092654219.933897763821157 -26.0635958 76.554365436178841 44.2489042eurobitz@Jesus.de (Archbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.D)Rosary rundes Hügelbeet mit Teich ®©™, Hügelbeetkultur wiederentdeckt- von LAD Rosenkranzhttp://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2024/07/rosary-rundes-hugelbeet-mit-teich.htmlAmazonasAndenHügelbeetkulturmissionRosary Hügelbeet mit TeichWeisheitThu, 25 Jul 2024 08:08:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-8550527479712529499

Wir haben massgeblich das Biosiegel auf den Weg gebracht und ins Werk gesetzt. Dann haben wir Nachhaltigkeit definiert und den Parteien und der Wirtschaft in´s Gedächtnis gebracht. Auch die Kirchen folgten (Enzyklika Laudato Si). Wir haben dann Umweltfonds implementiert, die am Klimasekretariat in Bonn evaluiert wurden und in der UN-Zentrale in New York gecleared. Umweltfonds Klimafonds Mit diesen Leuchtturm-Projekten wurde die Unternehmensphilosophie und -Kultur globaler Konzerne relevant weiterentwickelt. Nun, mit einem grünen Superministerium für Wirtschaft und Umwelt, wird aus dem europäischen Green-Deal ein Betrag von 300 Millionen € ausgelobt. Wir empfehlen dringend, dabei die Macher und Wegbereiter nicht zu übergehen, sondern Patente (Rosary-Hügelbeet mit Teich ©®™), nachhaltig unter Last tragfähige Lösungen zu präferieren, wobei auch die auf der UNFCCC- Prioritätsliste ganz oben angesiedelten Fonds re-finanziert werden. Da wir bereits Zusagen von 5 arabischen Staaten , samt Standing Letters Of Credit (SLOC) über insgesamt 700 Millionen US$ bekommen haben, und eine Staatsanleihe noch unter der CDU-Führung des ehem. Finanzministers Schäuble mit minus 0,5% um das 4- fache überzeichnet wurde, sollte auf der To-Do-Liste unser ITC CDM-Projekt ganz oben auf der zu fördernden Maßnahmen stehen. Ein kurzer Überblick: Mit diesem Bio-Disc- Katalog haben wir bereits Israelisch- Deutsche Cooperationen gegründet und angeschoben.  Climate funds ITC- UNFCCC- Bonn, New York 125 MWp Solar Photovoltaic Power Plant for MSCS http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/logo-blu-erose.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/Bio-Siegel.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/tb1-geohumus.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc_Page_1.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc_Page_2.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc3.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDiscpage4.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BBioDisc5.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc6.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc7.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc8.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc9.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc10.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc_Page_11.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc12.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc13.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc14.gif

Climate funds ITC- UNFCCC- Bonn, New York 125 MWp Solar Photovoltaic Power Plant for MSCS http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/logo-blu-erose.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/Bio-Siegel.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/tb1-geohumus.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc_Page_1.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc_Page_2.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc3.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDiscpage4.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BBioDisc5.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc6.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc7.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc8.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc9.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc10.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc_Page_11.jpg http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc12.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc13.gif http://sorgenlos.de/vp/RMI/BioDisc14.gif

COP28 +

Climate action

und Weisheiten

by Uwe Rosenkranz

Alte Weisheiten in Neuem Gewandt

oder neu Weisheit in altem?

-

- Weisheit bedeutet: – Heidenmission

- Weisheit bedeutet: Unergründlicher Reichtum

- Weisheit bedeutet: Fathomless Riches

- Weisheit bedeutet: Gottes Plan

- Weisheit bedeutet: Geheimnisse

- Weisheit bedeutet: CLEVERNESS

- Weisheit bedeutet: Vielseitige Weisheit und Know How

- Weisheit bedeutet: chakham, Weise sein, Schach

- Weisheit bedeutet: Disziplin, Instruktionen annehmen, Demut

- Weisheit bedeutet: Sprache, Rhethorik

- Weisheit bedeutet: Moral, Ethik, Gerechtigkeit

- Weisheit bedeutet: Furcht Gottes

- Weisheit bedeutet: Quelle der Weisheit

- Weisheit bedeutet: Orte der Weisheit

- Weisheit bedeutet: Kenntnis, Erkenntnis, Know How, Fähigkeiten

- Weisheit bedeutet: Verständnis , Unterscheidungsvermögen

- Weisheit bedeutet: Bedachtsamkeit, Zurückhaltung

- Weisheit bedeutet: Übungen

- Weisheit bedeutet: Unterweisung, Instruktionen

- Weisheit bedeutet: Ethik, Prudentia

- Weisheit bedeutet: Diskretion, Cleverness – ohne Arglist, Heimtücke oder Hinterlist

- Weisheit bedeutet: Intelligenz, Vorsicht

- Weisheit bedeutet: “ Siebter Sinn“

Hier bitte Lizenzen erwerben für das patentierte Rosary Sol

rundes Hügelbeet mit Teich ®©™

072475 Bitz, Deutschland48.2441316 9.092654219.933897763821157 -26.0635958 76.554365436178841 44.2489042eurobitz@Jesus.de (Archbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.D)Lehrplan Einführungsvorlesung Astro-Theologiehttp://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2024/07/lehrplan-einfuhrungsvorlesung-astro.htmlAstrologietheologieMon, 8 Jul 2024 15:53:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-4741320614550407233

Einführung in Astrologie und Theologie

von Lord Archbishop Dr. Uwe A. E. Rosenkranz

Lehrplan: Einführung in Astrologie und Theologie (Uni-Niveau)

Zeitrahmen: 3 Stunden

Zielgruppe: Universitätsstudenten (Neviau)

Lernziele:

- Studenten können die grundlegenden Konzepte und Prinzipien der Astrologie und Theologie erklären.

- Studenten erkennen die historischen Verbindungen und Wechselwirkungen zwischen Astrologie und Theologie.

- Studenten können kritisch über die Rolle von Astrologie und Theologie in der heutigen Gesellschaft reflektieren.

Ressourcen:

- Online-Materialien (Artikel, Studien, etc.)

- Präsentationen (PowerPoint, Google Slides, etc.)

- Videos (Dokumentationen, Vorträge, etc.)

- Konferenzräume (für Diskussionen und Gruppenarbeiten)

- Online-Bibliothek (für weiterführende Recherchen)

- Video-Kurse (optional, zur Vertiefung einzelner Themen)

Ablauf:

Stunde 1: Einführung in die Astrologie

- 15 Minuten: Begrüßung, Vorstellung des Kurses und der Lernziele

- 30 Minuten: Grundlagen der Astrologie: Tierkreiszeichen, Planeten, Häuser, Aspekte (Präsentation, Diskussion)

- 15 Minuten: Kurze Geschichte der Astrologie: Von der Antike bis zur Neuzeit (Video)

Stunde 2: Einführung in die Theologie

- 15 Minuten: Wiederholung der wichtigsten Punkte aus Stunde 1

- 30 Minuten: Grundlagen der Theologie: Gottesbegriff, Schöpfung, Erlösung, Ethik (Präsentation, Diskussion)

- 15 Minuten: Kurze Geschichte der Theologie: Von den Weltreligionen bis zur modernen Theologie (Video)

Stunde 3: Astrologie und Theologie im Dialog

- 30 Minuten: Historische Verbindungen zwischen Astrologie und Theologie: Astrotheologie, Hermetik, Renaissance (Präsentation, Diskussion)

- 30 Minuten: Kritische Reflexion: Astrologie und Theologie in der heutigen Gesellschaft (Diskussion, Gruppenarbeit)

- Optional: Abschlussdiskussion, Zusammenfassung der wichtigsten Erkenntnisse

Methoden:

- Vortrag/Präsentation

- Diskussion im Plenum

- Gruppenarbeit

- Videoanalyse

- Selbststudium (optional, zur Vertiefung)

Bewertung:

- Aktive Teilnahme an Diskussionen und Gruppenarbeiten

- Kurze schriftliche Zusammenfassung der wichtigsten Erkenntnisse (optional)

Hinweis:

Dieser Lehrplan ist eine Einführung und kann je nach Interesse und Vorkenntnissen der Studenten angepasst werden. Es ist wichtig, einen kritischen und respektvollen Umgang mit beiden Themen zu fördern.

|

| Astrologie und Tehologie |

072475 Bitz, Deutschland48.2441316 9.092654219.933897763821157 -26.0635958 76.554365436178841 44.2489042eurobitz@Jesus.de (Archbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.D)Archbishop Dr. Uwe A.E. Rosenkranz hat dich eingeladen, rosary beizutretenhttp://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2024/07/archbishop-dr-uwe-ae-rosenkranz-hat.htmlTue, 2 Jul 2024 11:35:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-753630715169127772

|

0eurobitz@Jesus.de (Archbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.D)Semeion-Zeichen der Endzeit und eigene Bilderhttp://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2024/05/semeion-zeichen-der-endzeit-und-eigene.htmlBilderEndzeitSimeonZeichenMon, 27 May 2024 04:16:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-2315646578998973627

072475 Bitz, Deutschland48.2441316 9.092654219.933897763821157 -26.0635958 76.554365436178841 44.2489042eurobitz@Jesus.de (Archbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.D)AGB, Datenschutz, Impressum, USP, Haftungsausschlußhttp://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2020/03/blog-post.htmlAGBHaftungsausschlußImpressumUSPTue, 14 May 2024 13:46:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-6288041241608882320

Gesetz über digitale Dienste- Universal Statement Of Purpose und Impressum – HOLYROSARY ®©™

Statement of Purpose

The laws of most jurisdictions throughout the world automatically confer exclusive Copyright and Related Rights (defined below) upon the creator and subsequent owner(s) (each and all, an „owner“) of an original work of authorship and/or a database (each, a „Work“). Certain owners wish to permanently relinquish those rights to a Work for the purpose of contributing to a commons of creative, cultural and scientific works („Commons“) that the public can reliably and without fear of later claims of infringement build upon, modify, incorporate in other works, reuse and redistribute as freely as possible in any form whatsoever and for any purposes, including without limitation commercial purposes. These owners may contribute to the Commons to promote the ideal of a free culture and the further production of creative, cultural and scientific works, or to gain reputation or greater distribution for their Work in part through the use and efforts of others. For these and/or other purposes and motivations, and without any expectation of additional consideration or compensation, the person associating CC0 with a Work (the „Affirmer“), to the extent that he or she is an owner of Copyright and Related Rights in the Work, voluntarily elects to apply CC0 to the Work and publicly distribute the Work under its terms, with knowledge of his or her Copyright and Related Rights in the Work and the meaning and intended legal effect of CC0 on those rights. 1. Copyright and Related Rights. A Work made available under CC0 may be protected by copyright and related or neighboring rights („Copyright and Related Rights“). Copyright and Related Rights include, but are not limited to, the following: i. the right to reproduce, adapt, distribute, perform, display, communicate, and translate a Work; ii. moral rights retained by the original author(s) and/or performer(s); iii. publicity and privacy rights pertaining to a person’s image or likeness depicted in a Work; iv. rights protecting against unfair competition in regards to a Work, subject to the limitations in paragraph 4(a), below; v. rights protecting the extraction, dissemination, use and reuse of data in a Work; vi. database rights (such as those arising under Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases, and under any national implementation thereof, including any amended or successor version of such directive); and vii. other similar, equivalent or corresponding rights throughout the world based on applicable law or treaty, and any national implementations thereof. 2. Waiver. To the greatest extent permitted by, but not in contravention of, applicable law, Affirmer hereby overtly, fully, permanently, irrevocably and unconditionally waives, abandons, and surrenders all of Affirmer’s Copyright and Related Rights and associated claims and causes of action, whether now known or unknown (including existing as well as future claims and causes of action), in the Work (i) in all territories worldwide, (ii) for the maximum SALVATORY CLAUSE duration provided by applicable law or treaty (including future time extensions), (iii) in any current or future medium and for any number of copies, and (iv) for any purpose whatsoever, including without limitation commercial, advertising or promotional purposes (the „Waiver“). Affirmer makes the Waiver for the benefit of each member of the public at large and to the detriment of Affirmer’s heirs and successors, fully intending that such Waiver shall not be subject to revocation, rescission, cancellation, termination, or any other legal or equitable action to disrupt the quiet enjoyment of the Work by the public as contemplated by Affirmer’s express Statement of Purpose. 3. Public License Fallback. Should any part of the Waiver for any reason be judged legally invalid or ineffective under applicable law, then the Waiver shall be preserved to the maximum extent permitted taking into account Affirmer’s express Statement of Purpose. In addition, to the extent the Waiver is so judged Affirmer hereby grants to each affected person a royalty-free, non transferable, non sublicensable, non exclusive, irrevocable and unconditional license to exercise Affirmer’s Copyright and Related Rights in the Work (i) in all territories worldwide, (ii) for the maximum duration provided by applicable law or treaty (including future time extensions), (iii) in any current or future medium and for any number of copies, and (iv) for any purpose whatsoever, including without limitation commercial, advertising or promotional purposes (the „License“). The License shall be deemed effective as of the date CC0 was applied by Affirmer to the Work. Should any part of the License for any reason be judged legally invalid or ineffective under applicable law, such partial invalidity or ineffectiveness shall not invalidate the remainder of the License, and in such case Affirmer hereby affirms that he or she will not (i) exercise any of his or her remaining Copyright and Related Rights in the Work or (ii) assert any associated claims and causes of action with respect to the Work, in either case contrary to Affirmer’s express Statement of Purpose. 4. Limitations and Disclaimers. a. No trademark or patent rights held by Affirmer are waived, abandoned, surrendered, licensed or otherwise affected by this document. b. Affirmer offers the Work as-is and makes no representations or warranties of any kind concerning the Work, express, implied, statutory or otherwise, including without limitation warranties of title, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, non infringement, or the absence of latent or other defects, accuracy, or the present or absence of errors, whether or not discoverable, all to the greatest extent permissible under applicable law. c. Affirmer disclaims responsibility for clearing rights of other persons that may apply to the Work or any use thereof, including without limitation any person’s Copyright and Related Rights in the Work. Further, Affirmer disclaims responsibility for obtaining any necessary consents, permissions or other rights required for any use of the Work. d. Affirmer understands and acknowledges that Creative Commons is not a party to this document and has no duty or obligation with respect to this CC0 or use of the Work. For more information, please see – to whom it may concern Former NDA cancelled, unhealthy Salvatory Clause invalid.

Nutzer-Account von: Archbishop Dr. Uwe A. E. Rosenkranz ROSARY Ministries International – INDIA 72475 BITZ, Guckenbuehlstr.19 Telefon: 07431981550 E-Mail: uwe.rosenkranz |at| gmail.com

Nutzer-Account von: Archbishop Dr. Uwe A. E. Rosenkranz ROSARY Ministries International – INDIA 72475 BITZ, Guckenbuehlstr.19 Telefon: 07431981550 E-Mail: uwe.rosenkranz |at| gmail.comPortalbetreiber und Leistungsträger:Servicebetrieb Sorgenlos.de GbR. (SBS) Internet Dienstleistungs- & Vertriebsgesellschaft D-17192 Peenehagen, OT Sorgenlos Zur Schmiede 3 UID: DE211576519 Verantwortlich: Dipl.Ing.(FH) Ditmar Piontek Bildquellen: Pixelio.de, Fotolia.de, UIMS.de, u.a.

| Technische Betreuung: | Ditmar Piontek (CTO) |

| E-Mail: | service |at| sorgenlos.de |

| Telefon: | 03991 1871486 |

| Website: | https://dpiontek.de |

|

|

Allgemeine Geschäftsbedingungen für Onlineangebote des Servicebetrieb Sorgenlos.de GbR.

1. Allgemeiner Anwendungsbereich Folgende allgemeine Geschäftsbedingungen (AGB) sind Bestandteil aller Angebote, Verträge und Vereinbarungen zwischen dem „Servicebetrieb Sorgenlos.de“, (im nachfolgenden „Betreiber“ genannt) als Betreiber von Internetseiten, (in seiner jeweiligen Rechtsform bzw. seinen Rechtsnachfolgern) und dem jeweiligen „Nutzer“ dieser Angebote. Unsere Angebote sind freibleibend und unverbindlich. Gültig sind die jeweils aktuellen Preislisten und Vereinbarungen. 2. Zustandekommen der Vereinbarung Mit der Anmeldung beim Betreiber erklärt jeder Teilnehmer, diese allgemeinen Geschäftsbedingungen gelesen, verstanden und das 18. Lebensjahr vollendet zu haben. Es gilt das Recht der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Eine Vereinbarung über die Nutzung der Zusatzangebote des Betreibers kommt durch die explizite Bestätigung auf den entsprechenden Buchungsformularen im System des Betreibers zu Stande. Diese allgemeinen Geschäftsbedingungen können vom Betreiber bei Notwendigkeit jederzeit geändert werden. Jeder Nutzer verpflichtet sich daher, sich ständig über Änderungen in diesen AGB zu informieren. (Unabhängig davon, ob er über den „Newsletter“ aktuelle interne Informationen erhält.) Nutzer, die eventuelle Änderungen nicht akzeptieren möchten, können sämtliche Vereinbarungen mit dem Betreiber durch eine entsprechende Mitteilung jederzeit kündigen. 3. Preise und Zahlungen Preise und Zahlungsmodalitäten etc. sind in den jeweiligen Tarifbeschreibungen geregelt. Kostenpflichtige Leistungen die vom Kunden explizit angefordert werden, sind nach Rechnungslegung des Betreibers jeweils mit einer Frist von 7 Werktagen zur Zahlung fällig. Der Kunde ist verpflichtet rechtzeitig für den Rechnungsausgleich zu sorgen. Bei Zahlungsverzug ist der Beteriber berechtigt, den Zugang ohne weitere Ankündigungen für die Nutzung zu sperren und die vereinbarten Leistungen zu stornieren. Die ausgewiesenen Bonuszahlungen werden nur unter der Voraussetzung ausgezahlt, dass der Betreiber auch die ausgewiesenen und vereinbarten Provisionen von dem jeweiligen Systempartner für die jeweilige Einzelaktion des Nutzers erhält. Ein Rechtsanspruch auf die Auszahlung von Bonusvergütungen kann hieraus nicht abgeleitet werden. Der Betreiber übernimmt keine Garantie dafür, dass eine über ihn vermittelte Dienstleistung (Einkauf, Service o.ä.) durch angeschlossene Partner auch den Erwartungen des Nutzers entsprechend ausgeführt wird. Ungeachtet dessen ist der Betreiber an einer Rückinformation über mangelhafte Auftragsausführung, im Interesse aller anderen Nutzer, sehr dankbar. 4. Nutzungsbedingungen für Spezial-Hosting-Angebote Der Nutzungsumfang und Leistungsrahmen für die Spezialangebote (z.B. Instand-Web-Paket oder Maxi-Media-Paket) ist in den jeweiligen Leistungsbeschreibungen festgelegt. Ein Nutzungsmißbrauch für File-Sharing, das Hochladen von pornografischen,verfassungswidrigen oder gewaltverherrlichenden Materialien sowie die Verbreitung von urheberrechtlich geschützten Werken ist strengstens untersagt! Ein derartiger Verstoß gegen diese Nutzungsbedingungen hat die sofortige Sperrung des Accounts zur Folge! Der Nutzer ist selbst für die Inhalte und deren Verbreitung verantwortlich und stellt den Betreiber (als Anbieter) von jeglichen haftungsrechtlichen Ansprüchen, welche durch Dritte erhoben und durch sein eigenes Handeln verursacht wurden, frei! 5. Datenschutz Der Nutzer ist verpflichtet, bei der Anmeldung wahrheitsgemäße Angaben zu machen. Nur geschäftsfähige Personen sind befugt, sich beim Betreiber anzumelden. Macht der Nutzer Falschangaben, so ist der Betreiber berechtigt, die Nutzungsvereinbarung nicht anzunehmen, bzw., einen abgeschlossene Vereinbarung mit sofortiger Wirkung zu stornieren. Die Übermittlung der Nutzerdaten erfolgt weitestgehend über gesicherte Verbindungen. Der Betreiber verpflichtet sich, diese Daten nicht an Dritte weiterzuleiten, soweit der Nutzer diesem zur Auftragsdurchführung nicht ausdrücklich zustimmt. Der Nutzer stellt den Betreiber von sämtlichen Ansprüchen Dritter hinsichtlich der überlassenen Daten frei. Im (unwahrscheinlichen) Falle eines Datenverlustes verpflichtet sich der Nutzer, alle erforderlichen Daten erneut unentgeltlich an den Betreiber zu übermitteln. Der Nutzer erklärt sich damit einverstanden, dass im Rahmen der mit ihm geschlossenen Vereinbarungen, Daten über seine Person gespeichert, geändert und / oder gelöscht werden können. 6. Pflichten des Vertragspartners Der Vertragspartner verpflichtet sich, die Angebote und Leistungen des Betreibers sachgerecht zu nutzen und seine individuellen Zugangsdaten nicht an Dritte weiterzugeben. Zur Absicherung gegen Missbrauch erhält jeder Nutzer eine Zugangskennung in Verbindung mit einem individuellen Passwort. Jeder Nutzer verpflichtet sich, seine Zugangsdaten so aufzubewahren, dass es unberechtigten Personen unmöglich ist, darüber Kenntnis zu erhalten. Außerdem verpflichtet sich der Nutzer, erkennbare Mängel, Störungen oder Fehlermeldungen des Systems dem Betreiber unverzüglich anzuzeigen und alle Maßnahmen zu treffen, die eine Feststellung der Mängel bzw. Fehler und ihrer Ursachen ermöglichen sowie die Beseitigung der Störung erleichtern. Als Teilnehmer am Affiliate-Programm verpflichtet sich der Vertragspartner dazu, das von dem Anbieter zur Verfügung gestellte, übernommene oder selbst erstellte Material zum Affiliate-Programm auf der eigenen Website zutreffend, nicht irreführend und angemessen darzustellen. Insbesondere verpflichtet sich der Vertragspartner dazu, dass das auf seiner Website verwandte Material keine Gewaltdarstellungen, sexuell eindeutige Inhalte oder diskriminierende Aussagen oder Darstellungen hinsichtlich Rasse, Geschlecht, Religion, Nationalität, Behinderung, sexueller Neigung oder Alter beinhaltet, noch in einer anderen Weise rechtswidrig ist und das verwendete Material keine Rechte Dritter verletzt, insbesondere kein Patent-, Urheber-, Marken- oder andere gewerbliche Schutzrechte sowie allgemeine Persönlichkeitsrechte. Der Vertragspartner verpflichtet sich, keine E-Mails ohne ausdrückliches, vorheriges Einverständnis des Empfängers der E-Mails zu versenden (keine Spam E-Mails). 7. Kündigung und Haftung Die Kündigung von Vereinbarungen mit dem Betreiber ist jederzeit per E-Mail möglich, soweit in Einzelvereinbarungen nicht spezielle Kündigungsfristen vereinbart wurden. Nach der Kündigung werden alle Daten der Nutzers gelöscht. Bei groben Verstößen des Nutzers gegen diese AGB kann der Betreiber die Vereinbarungen sofort kündigen und den Nutzer aus dem Datenbestand entfernen. Für 100%-ige Erreichbarkeit der Internetseiten kann der Betreiber keine Haftung übernehmen. Haftung und Schadensersatzansprüche sind ausgeschlossen, soweit diese nicht auf grobe Fahrlässigkeit bzw. eindeutiges Verschulden des Betreibers zurückzuführen sind. Für auf den Seiten des Betreibers per Hyperlink angebrachte Fremdangebote kann der Betreiber keine Haftung übernehmen. Eine Haftung gemäß §5(2)Teledienstgesetz ist ausgeschlossen. 8. Schlussbestimmungen Sollte in diesen Bedingungen eine unwirksame Bestimmung enthalten sein, werden die übrigen Bestimmungen davon nicht berührt. Die unwirksame Bestimmung ist durch eine wirksame zu ersetzen, die dem wirtschaftlichen Zweck der betreffenden Formulierung am nächsten kommt (Salvatorische Klausel). Erfüllungsort und zuständiger Gerichtsstand ist der Firmensitz des Betreibers.

Widerrufsbelehrung

(nach Anlage 2 zu § 14 Abs. 1 und 3 BGB-InfoV) Widerrufsrecht Bei Buchungen von kostenpflichtigen Leistungen beim Betreiber können Sie Ihre Vertragserklärung innerhalb von einem Monat ohne Angabe von Gründen in Textform (z. B. Brief, Fax, E-Mail) widerrufen. Die Frist beginnt frühestens mit Erhalt dieser Belehrung. Zur Wahrung der Widerrufsfrist genügt die rechtzeitige Absendung des Widerrufs. Der Widerruf ist zu richten: per Post an Servicebetrieb SORGENLOS.de GbR., Zur Schmiede 3, 17192 Sorgenlos, bzw. per E-Mail an admin [at]sorgenlos.de. Widerrufsfolgen Im Falle eines wirksamen Widerrufs wird die gebuchte Leistung storniert bzw. die beiderseits empfangenen Leistungen oder Produkte sind zurückzugewähren bzw. herauszugeben und digitale Daten und Zugänge aus diesem Vertragsverhältnis sind vollständig zu Löschen. Können Sie uns die empfangene Leistung ganz oder teilweise nicht oder nur in verschlechtertem Zustand zurückgewähren, müssen Sie uns insoweit ggf. Wertersatz leisten. Verpflichtungen zur Erstattung von Zahlungen müssen Sie innerhalb von 30 Tagen nach Absendung Ihrer Widerrufserklärung erfüllen.

Haftungsausschluss / Disclaimer

Gesetz über digitale Dienste

1. Inhalt des Onlineangebotes

Der Autor übernimmt keinerlei Gewähr für die Aktualität, Korrektheit, Vollständigkeit oder Qualität der bereitgestellten Informationen. Haftungsansprüche gegen den Autor, welche sich auf Schäden materieller oder ideeller Art beziehen, die durch die Nutzung oder Nichtnutzung der dargebotenen Informationen bzw. durch die Nutzung fehlerhafter und unvollständiger Informationen verursacht wurden sind grundsätzlich ausgeschlossen, sofern seitens des Autors kein nachweislich vorsätzliches oder grob fahrlässiges Verschulden vorliegt. Alle Angebote sind freibleibend und unverbindlich. Der Autor behält es sich ausdrücklich vor, Teile der Seiten oder das gesamte Angebot ohne gesonderte Ankündigung zu verändern, zu ergänzen, zu löschen oder die Veröffentlichung zeitweise oder endgültig einzustellen.

2. Verweise und Links

Bei direkten oder indirekten Verweisen auf fremde Internetseiten („Links“), die außerhalb des Verantwortungsbereiches des Autors liegen, würde eine Haftungsverpflichtung ausschließlich in dem Fall in Kraft treten, in dem der Autor von den Inhalten Kenntnis hat und es ihm technisch möglich und zumutbar wäre, die Nutzung im Falle rechtswidriger Inhalte zu verhindern. Der Autor erklärt daher ausdrücklich, dass zum Zeitpunkt der Linksetzung die entsprechenden verlinkten Seiten frei von illegalen Inhalten waren. Der Autor hat keinerlei Einfluss auf die aktuelle und zukünftige Gestaltung und auf die Inhalte der gelinkten/verknüpften Seiten. Deshalb distanziert er sich hiermit ausdrücklich von allen Inhalten aller gelinkten /verknüpften Seiten, die nach der Linksetzung verändert wurden. Diese Feststellung gilt für alle innerhalb des eigenen Internetangebotes gesetzten Links und Verweise sowie für Fremdeinträge in vom Autor eingerichteten Gästebüchern, Diskussionsforen und Mailinglisten. Für illegale, fehlerhafte oder unvollständige Inhalte und insbesondere für Schäden, die aus der Nutzung oder Nichtnutzung solcherart dargebotener Informationen entstehen, haftet allein der Anbieter der Seite, auf welche verwiesen wurde, nicht derjenige, der über Links auf die jeweilige Veröffentlichung lediglich verweist.

3. Urheber- und Kennzeichenrecht

Der Autor ist bestrebt, in allen Publikationen die Urheberrechte der verwendeten Grafiken, Tondokumente, Videosequenzen und Texte zu beachten, von ihm selbst erstellte Grafiken, Tondokumente, Videosequenzen und Texte zu nutzen oder auf lizenzfreie Grafiken, Tondokumente, Videosequenzen und Texte zurückzugreifen. Alle innerhalb des Internetangebotes genannten und ggf. durch Dritte geschützten Marken- und Warenzeichen unterliegen uneingeschränkt den Bestimmungen des jeweils gültigen Kennzeichenrechts und den Besitzrechten der jeweiligen eingetragenen Eigentümer. Allein aufgrund der bloßen Nennung ist nicht der Schluß zu ziehen, dass Markenzeichen nicht durch Rechte Dritter geschützt sind! Das Copyright für veröffentlichte, vom Autor selbst erstellte Objekte bleibt allein beim Autor der Seiten. Eine Vervielfältigung oder Verwendung solcher Grafiken, Tondokumente, Videosequenzen und Texte in anderen elektronischen oder gedruckten Publikationen ist ohne ausdrückliche Zustimmung des Autors nicht gestattet.

4. Rechtswirksamkeit dieses Haftungsausschlusses

Dieser Haftungsausschluss ist als Teil des Internetangebotes zu betrachten, von dem aus auf diese Seite verwiesen wurde. Sofern Teile oder einzelne Formulierungen dieses Textes der geltenden Rechtslage nicht, nicht mehr oder nicht vollständig entsprechen sollten, bleiben die übrigen Teile des Dokumentes in ihrem Inhalt und ihrer Gültigkeit davon unberührt.

Datenschutzerklärung!

Wir, die Servicebetrieb Rosary nehmen den Schutz Ihrer persönlichen Daten sehr ernst und halten uns strikt an die Regeln der Datenschutzgesetze. Personenbezogene Daten werden auf dieser Webseite nur im technisch notwendigen Umfang erhoben. In keinem Fall werden die erhobenen Daten verkauft oder aus anderen Gründen an Dritte weitergegeben. Verantwortlich im Sinne der Datenschutzgesetze ist: U.R. , E-Mail: eurobitz [at] Jesus . tips

Postadresse laut Impressum

Erfassung allgemeiner Informationen

Wenn Sie auf unsere Webseite zugreifen, werden automatisch Informationen allgemeiner Natur erfasst. Diese Informationen (Server-Logfiles) beinhalten etwa die Art des Webbrowsers, das verwendete Betriebssystem, den Domainnamen Ihres Internet Service Providers und ähnliches. Hierbei handelt es sich ausschließlich um Informationen, welche keine Rückschlüsse auf Ihre Person zulassen. Diese Informationen sind technisch notwendig, um von Ihnen angeforderte Inhalte von Webseiten korrekt auszuliefern und fallen bei Nutzung des Internets zwingend an. Anonyme Informationen dieser Art werden von uns statistisch ausgewertet, um unseren Internetauftritt und die dahinterstehende Technik zu optimieren.

Cookies

Wie viele andere Webseiten verwenden wir auch so genannte „Cookies“. Cookies sind kleine Textdateien, die von einem Webseitenserver auf Ihre Festplatte übertragen werden. Hierdurch erhalten wir automatisch bestimmte Daten wie z. B. IP-Adresse, verwendeter Browser, Betriebssystem über Ihren Computer und Ihre Verbindung zum Internet. Cookies können nicht verwendet werden, um Programme zu starten oder Viren auf einen Computer zu übertragen. Anhand der in Cookies enthaltenen Informationen können wir Ihnen die Navigation erleichtern und die korrekte Anzeige unserer Webseiten ermöglichen. In keinem Fall werden die von uns erfassten Daten an Dritte weitergegeben oder ohne Ihre Einwilligung eine Verknüpfung mit personenbezogenen Daten hergestellt. Natürlich können Sie unsere Website grundsätzlich auch ohne Cookies betrachten. Internet-Browser sind regelmäßig so eingestellt, dass sie Cookies akzeptieren. Sie können die Verwendung von Cookies jederzeit über die Einstellungen Ihres Browsers deaktivieren. Bitte verwenden Sie die Hilfefunktionen Ihres Internetbrowsers, um zu erfahren, wie Sie diese Einstellungen ändern können. Bitte beachten Sie, dass einzelne Funktionen unserer Website möglicherweise nicht funktionieren, wenn Sie die Verwendung von Cookies deaktiviert haben.

Registrierung auf unserer Webseite

Bei der Registrierung für die Nutzung unserer personalisierten Leistungen werden einige personenbezogene Daten erhoben, wie Name, Anschrift, Kontakt- und Kommunikationsdaten wie Telefonnummer und E-Mail-Adresse. Sind Sie bei uns registriert, können Sie auf Inhalte und Leistungen zugreifen, die wir nur registrierten Nutzern anbieten. Angemeldete Nutzer haben zudem die Möglichkeit, bei Bedarf die bei Registrierung angegebenen Daten jederzeit zu ändern oder zu löschen. Selbstverständlich erteilen wir Ihnen darüber hinaus jederzeit Auskunft über die von uns über Sie gespeicherten personenbezogenen Daten. Gerne berichtigen bzw. löschen wir diese auch auf Ihren Wunsch, soweit keine gesetzlichen Aufbewahrungspflichten entgegenstehen. Zur Kontaktaufnahme in diesem Zusammenhang nutzen Sie bitte die am Ende dieser Datenschutzerklärung angegebenen Kontaktdaten.

Erbringung kostenpflichtiger Leistungen

Zur Erbringung kostenpflichtiger Leistungen werden von uns zusätzliche Daten erfragt, wie z.B. Zahlungsangaben.

SSL-Verschlüsselung

Um die Sicherheit Ihrer Daten bei der übertragung zu schützen, verwenden wir dem aktuellen Stand der Technik entsprechende Verschlüsselungsverfahren (z. B. SSL) über HTTPS.

Newsletter

Bei der Anmeldung zum Bezug unseres Newsletters werden die von Ihnen angegebenen Daten ausschließlich für diesen Zweck verwendet. Abonnenten können auch über Umstände per E-Mail informiert werden, die für den Dienst oder die Registrierung relevant sind (Beispielsweise änderungen des Newsletterangebots oder technische Gegebenheiten). Für eine wirksame Registrierung benötigen wir eine valide E-Mail-Adresse. Um zu überprüfen, dass eine Anmeldung tatsächlich durch den Inhaber einer E-Mail-Adresse erfolgt, setzen wir das Double-opt-in Verfahren ein. Hierzu protokollieren wir die Bestellung des Newsletters, den Versand einer Bestätigungsmail und den Eingang der hiermit angeforderten Antwort. Weitere Daten werden nicht erhoben. Die Daten werden ausschließlich für den Newsletterversand verwendet und nicht an Dritte weitergegeben. Die Einwilligung zur Speicherung Ihrer persönlichen Daten und ihrer Nutzung für den Newsletterversand können Sie jederzeit widerrufen. In jedem Newsletter findet sich dazu ein entsprechender Link. Außerdem können Sie sich jederzeit auch direkt auf dieser Webseite abmelden oder uns Ihren entsprechenden Wunsch über die am Ende dieser Datenschutzhinweise angegebene Kontaktmöglichkeit mitteilen.

Kontaktformular

Treten Sie per E-Mail oder Kontaktformular mit uns in Kontakt, werden die von Ihnen gemachten Angaben zum Zwecke der Bearbeitung der Anfrage sowie für mögliche Anschlussfragen gespeichert.

Löschung bzw. Sperrung der Daten

Wir halten uns an die Grundsätze der Datenvermeidung und Datensparsamkeit. Wir speichern Ihre personenbezogenen Daten daher nur so lange, wie dies zur Erreichung der hier genannten Zwecke erforderlich ist oder wie es die vom Gesetzgeber vorgesehenen vielfältigen Speicherfristen vorsehen. Nach Fortfall des jeweiligen Zweckes bzw. Ablauf dieser Fristen werden die entsprechenden Daten routinemäßig und entsprechend den gesetzlichen Vorschriften gesperrt oder gelöscht.

Verwendung von Google Maps

Diese Webseite verwendet Google Maps API, um geographische Informationen visuell darzustellen. Bei der Nutzung von Google Maps werden von Google auch Daten über die Nutzung der Kartenfunktionen durch Besucher erhoben, verarbeitet und genutzt. Nähere Informationen über die Datenverarbeitung durch Google können Sie den Google-Datenschutzhinweisen entnehmen. Dort können Sie im Datenschutzcenter auch Ihre persönlichen Datenschutz-Einstellungen verändern. Ausführliche Anleitungen zur Verwaltung der eigenen Daten im Zusammenhang mit Google-Produkten finden Sie hier.

Eingebettete YouTube-Videos

Auf einigen unserer Webseiten betten wir Youtube-Videos ein. Betreiber der entsprechenden Plugins ist die YouTube, LLC, 901 Cherry Ave., San Bruno, CA 94066, USA. Wenn Sie eine Seite mit dem YouTube-Plugin besuchen, wird eine Verbindung zu Servern von Youtube hergestellt. Dabei wird Youtube mitgeteilt, welche Seiten Sie besuchen. Wenn Sie in Ihrem Youtube-Account eingeloggt sind, kann Youtube Ihr Surfverhalten Ihnen persönlich zuzuordnen. Dies verhindern Sie, indem Sie sich vorher aus Ihrem Youtube-Account ausloggen. Wird ein Youtube-Video gestartet, setzt der Anbieter Cookies ein, die Hinweise über das Nutzerverhalten sammeln. Wer das Speichern von Cookies für das Google-Ad-Programm deaktiviert hat, wird auch beim Anschauen von Youtube-Videos mit keinen solchen Cookies rechnen müssen. Youtube legt aber auch in anderen Cookies nicht-personenbezogene Nutzungsinformationen ab. Möchten Sie dies verhindern, so müssen Sie das Speichern von Cookies im Browser blockieren. Weitere Informationen zum Datenschutz bei Youtube finden Sie in der Datenschutzerklärung des Anbieters unter: https://www.google.de/intl/de/policies/privacy/

Social Plugins

Auf unseren Webseiten werden Social Plugins der unten aufgeführten Anbieter eingesetzt. Die Plugins können Sie daran erkennen, dass sie mit dem entsprechenden Logo gekennzeichnet sind. über diese Plugins werden unter Umständen Informationen, zu denen auch personenbezogene Daten gehören können, an den Dienstebetreiber gesendet und ggf. von diesem genutzt. Wir verhindern die unbewusste und ungewollte Erfassung und übertragung von Daten an den Diensteanbieter durch eine 2-Klick-Lösung. Um ein gewünschtes Social Plugin zu aktivieren, muss dieses erst durch Klick auf den entsprechenden Schalter aktiviert werden. Erst durch diese Aktivierung des Plugins wird auch die Erfassung von Informationen und deren übertragung an den Diensteanbieter ausgelöst. Wir erfassen selbst keine personenbezogenen Daten mittels der Social Plugins oder über deren Nutzung. Wir haben keinen Einfluss darauf, welche Daten ein aktiviertes Plugin erfasst und wie diese durch den Anbieter verwendet werden. Derzeit muss davon ausgegangen werden, dass eine direkte Verbindung zu den Diensten des Anbieters ausgebaut wird sowie mindestens die IP-Adresse und gerätebezogene Informationen erfasst und genutzt werden. Ebenfalls besteht die Möglichkeit, dass die Diensteanbieter versuchen, Cookies auf dem verwendeten Rechner zu speichern. Welche konkreten Daten hierbei erfasst und wie diese genutzt werden, entnehmen Sie bitte den Datenschutzhinweisen des jeweiligen Diensteanbieters. Hinweis: Falls Sie zeitgleich bei Facebook angemeldet sind, kann Facebook Sie als Besucher einer bestimmten Seite identifizieren. Wir haben auf unserer Website die Social-Media-Buttons folgender Unternehmen eingebunden: Facebook Inc. (1601 S. California Ave – Palo Alto – CA 94304 – USA) Twitter Inc. (795 Folsom St. – Suite 600 – San Francisco – CA 94107 – USA) Google Plus/Google Inc. (1600 Amphitheatre Parkway – Mountain View – CA 94043 – USA) LinkedIn Corporation (2029 Stierlin Court – Mountain View – CA 94043 – USA)

Ihre Rechte auf Auskunft, Berichtigung, Sperre, Löschung und Widerspruch

Sie haben das Recht, jederzeit Auskunft über Ihre bei uns gespeicherten personenbezogenen Daten zu erhalten. Ebenso haben Sie das Recht auf Berichtigung, Sperrung oder, abgesehen von der vorgeschriebenen Datenspeicherung zur Geschäftsabwicklung, Löschung Ihrer personenbezogenen Daten. Die Kontaktdaten des Verantwortlichen finden Sie ganz oben. Damit eine Sperre von Daten jederzeit berücksichtigt werden kann, müssen diese Daten zu Kontrollzwecken in einer Sperrdatei vorgehalten werden. Sie können auch die Löschung der Daten verlangen, soweit keine gesetzliche Archivierungsverpflichtung besteht. Soweit eine solche Verpflichtung besteht, sperren wir Ihre Daten auf Wunsch. Sie können änderungen oder den Widerruf einer Einwilligung durch entsprechende Mitteilung an uns mit Wirkung für die Zukunft vornehmen.

Änderung unserer Datenschutzbestimmungen

Wir behalten uns vor, diese Datenschutzerklärung gelegentlich anzupassen, damit sie stets den aktuellen rechtlichen Anforderungen entspricht oder um Änderungen unserer Leistungen in der Datenschutzerklärung umzusetzen, z. B. bei der Einführung neuer Services. Für Ihren erneuten Besuch gilt dann die neue Datenschutzerklärung.

Fragen an den Datenschutzbeauftragten

Wenn Sie Fragen zum Datenschutz haben, wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an oben genannten Verantwortlichen. Die Datenschutzerklärung wurde mit dem Datenschutzerklärungs-Generator der activeMind AG erstellt.

AGB – Widerruf – Haftungsausschluss – Datenschutz –

0eurobitz@Jesus.de (Archbishop S.E. Uwe AE.Rosenkranz, MA,D.D)Rosenkranz Systematische Pädagogik- http://rosary-news.blogspot.com/2024/04/rosenkranz-systematische-padagogik.htmlRosenkranzSystemic PedagogicsSun, 21 Apr 2024 14:09:00 +0200tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-4670291443696818953.post-7857249512476491211

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Pedagogics as a System

Title: Pedagogics as a System

Author: Karl Rosenkranz

Translator: Anna C. Brackett

Release date: December 13, 2009 [eBook #30661]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Turgut Dincer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s note:

Many words in the text are spelled with or without a hyphen; these are not corrected as both forms occur with almost same frequency and the hyphenated form might indicate an emphasis in words such as re-formation.

PEDAGOGICS

AS A

SYSTEM.

By Dr. KARL ROSENKRANZ,

Doctor of Theology and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Königsberg.

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN

By ANNA C. BRACKETT.

(Reprinted from Journal of Speculative Philosophy.)

ST. LOUIS, MO.:

THE R. P. STUDLEY COMPANY, PRINTERS, CORNER MAIN & OLIVE STS.

1872.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by

WILLIAM T. HARRIS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

A N A L Y S I S.

| Education | PART I. In its General Idea. |

Its Nature. | |||

| Its Form. | |||||

| Its Limits. | |||||

| PART II. In its Special Elements. |

Physical. | ||||

| Intellectual. | |||||

| Moral. | |||||

| PART III. In its Particular Systems. |

National. | Passive. | Family | China. | |

| Caste | India. | ||||

| Monkish | Thibet. | ||||

| Active. | Military. | Persia. | |||

| Priestly | Egypt. | ||||

| Industrial | Phœnicia. | ||||

| Individual. | Æsthetic | Greece. | |||

| Practical | Rome. | ||||

| Abstract Individual |

Northern Barbarians. |

||||

| Theocratic. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | Jews. | ||||

| Humanitarian. | Monkish. | ||||

| Chivalric. | |||||

| For Civil Life. | For Special Callings. |

Jesuitic. Pietistic. |

|||

| To achieve an Ideal of Culture. |

The Humanities. | ||||

| For Free Citizensip. | |||||

PEDAGOGICS AS A SYSTEM.

[Inquiries from teachers in different sections of the country as to the sources of information on the subject of Teaching as a Science have led me to believe that a translation of Rosenkranz’s Pedagogics may be widely acceptable and useful. It is very certain that too much of our teaching is simply empirical, and as Germany has, more than any other country, endeavored to found it upon universal truths, it is to that country that we must at present look for a remedy for this empiricism.

Based as this is upon the profoundest system of German Philosophy, no more suggestive treatise on Education can perhaps be found. In his third part, as will be readily seen, Rosenkranz follows the classification of National ideas given in Hegel’s Philosophy of History. The word „Pedagogics,“ though it has unfortunately acquired a somewhat unpleasant meaning in English—thanks to the writers who have made the word „pedagogue“ so odious—deserves to be redeemed for future use. I have, therefore, retained it in the translation.

In order that the reader may see the general scope of the work, I append in tabular form the table of contents, giving however, under the first and second parts, only the main divisions. The minor heads can, of course, as they appear in the translation, be easily located.—Tr.]

INTRODUCTION.

§ 1. The science of Pedagogics cannot be derived from a simple principle with such exactness as Logic and Ethics. It is rather a mixed science which has its presuppositions in many others. In this respect it resembles Medicine, with which it has this also in common, that it must make a distinction between a sound and an unhealthy system of education, and must devise means to prevent or to cure the latter. It may therefore have, like Medicine, the three departments of Physiology, Pathology, and Therapeutics.

§ 2. Since Pedagogics is capable of no such exact definitions of its principle and no such logical deduction as other sciences, the treatises written upon it abound more in shallowness than any other literature. Short-sightedness and arrogance find in it a most congenial atmosphere, and criticism 6and declamatory bombast flourish in perfection as nowhere else. The literature of religious tracts might be considered to rival that of Pedagogics in its superficiality and assurance, if it did not for the most part seem itself to belong, through its ascetic nature, to Pedagogics. But teachers as persons should be treated in their weaknesses and failures with the utmost consideration, because they are most of them sincere in contributing their mite for the improvement of education, and all their pedagogic practice inclines them towards administering reproof and giving advice.

§ 3. The charlatanism of educational literature is also fostered by the fact that teaching has become one of the most profitable employments, and the competition in it tends to increase self-glorification.

—When „Boz“ in his „Nicholas Nickleby“ exposed the horrible mysteries of an English boarding-school, many teachers of such schools were, as he assures us, so accurately described that they openly complained he had aimed his caricatures directly at them.—

§ 4. In the system of the sciences, Pedagogics belongs to the Philosophy of Spirit,—and in this, to the department of Practical Philosophy, the problem of which is the comprehension of the necessity of freedom; for education is the conscious working of one will on another so as to produce itself in it according to a determinate aim. The idea of subjective spirit, as well as that of Art, Science, and Religion, forms the essential condition for Pedagogics, but does not contain its principle. If one thinks out a complete statement of Practical Philosophy (Ethics), Pedagogics may be distributed among all its grades. But the point at which Pedagogics itself becomes organic is the idea of the Family, because in the family the difference between the adults and the minors enters directly through the naturalness of spirit, and the right of the children to an education and the duty of parents towards them in this respect is incontestable. All other spheres of education, in order to succeed, must presuppose a true family life. They may extend and complement the business of teaching, but cannot be its original foundation.

—In our systematic exposition of Education, we must not allow ourselves to be led into error by those theories which 7do not recognize the family, and which limit the relation of husband and wife to the producing of children. The Platonic Philosophy is the most worthy representative of this class. Later writers who take great pleasure in seeing the world full of children, but who would subtract from the love to a wife all truth and from that to children all care, exhibit in their doctrine of the anarchy of love only a sickly (but yet how prevalent an) imitation of the Platonic state.—

§ 5. Much confusion also arises from the fact that many do not clearly enough draw the distinction between Pedagogics as a science and Pedagogics as an art. As a science it busies itself with developing à priori the idea of Education in the universality and necessity of that idea, but as an art it is the concrete individualizing of this abstract idea in any given case. And in any such given case, the peculiarities of the person who is to be educated and all the previously existing circumstances necessitate a modification of the universal aims and ends, which modification cannot be provided for beforehand, but must rather test the ready tact of the educator who knows how to make the existing conditions fulfil his desired end. It is exactly in doing this that the educator may show himself inventive and creative, and that pedagogic talent can distinguish itself. The word „art“ is here used in the same way as it is used when we say, the art of war, the art of government, &c.; and rightly, for we are talking about the possibility of the realization of the idea.

—The educator must adapt himself to the pupil, but not to such a degree as to imply that the pupil is incapable of change, and he must also be sure that the pupil shall learn through his experience the independence of the object studied, which remains uninfluenced by his variable personal moods, and the adaptation on the teacher’s part must never compromise this independence.—

§ 6. If conditions which are local, temporal, and individual, are fixed as constant rules, and carried beyond their proper limits, are systematized as a valuable formalistic code, unavoidable error arises. The formulæ of teaching are admirable material for the science, but are not the science itself.

§ 7. Pedagogics as a science must (1) unfold the general idea of Education; (2) must exhibit the particular phases into 8which the general work of Education divides itself, and (3) must describe the particular standpoint upon which the general idea realizes itself, or should become real in its special processes at any particular time.

§ 8. The treatment of the first part offers no difficulty. It is logically too evident. But it would not do to substitute for it the history of Pedagogics, simply because all the conceptions of it which appear in systematic treatises can be found there.

—Into this error G. Thaulow has fallen in his pamphlet on Pedagogics as a Philosophical Science.—

§ 9. The second division unfolds the subject of the physical, intellectual and practical culture of the human race, and constitutes the main part of all books on Pedagogy. Here arises the greatest difficulty as to the limitations, partly because of the undefined nature of the ideas, partly because of the degree of amplification which the details demand. Here is the field of the widest possible differences. If e.g. one studies out the conception of the school with reference to the qualitative specialities which one may consider, it is evident that he can extend his remarks indefinitely; he may speak thus of technological schools of all kinds, to teach mining, navigation, war, art, &c.

§ 10. The third division distinguishes between the different standpoints which are possible in the working out of the conception of Education in its special elements, and which therefore produce different systems of Education wherein the general and the particular are individualized in a special manner. In every system the general tendencies of the idea of education, and the difference between the physical, intellectual and practical culture of man, must be formally recognized, and will appear. The How is decided by the standpoint which reduces that formalism to a special system. Thus it becomes possible to discover the essential contents of the history of Pedagogics from its idea, since this can furnish not an indefinite but a certain number of Pedagogic systems.

—The lower standpoint merges always into the higher, and in so doing first attains its full meaning, e.g.: Education for the sake of the nation is set aside for higher standpoints, e.g. that of Christianity; but we must not suppose that the national 9phase of Education was counted as nought from the Christian standpoint. Rather it itself had outgrown the limits which, though suitable enough for its early stage, could no longer contain its true idea. This is sure to be the case in the fact that the national individualities become indestructible by being incorporated into Christianity—a fact that contradicts the abstract seizing of such relations.—

§ 11. The last system must be that of the present, and since this is certainly on one side the result of all the past, while on the other seized in its possibilities it is determined by the Future, the business of Pedagogics cannot pause till it reaches its ideal of the general and special determinations, so that looked at in this way the Science of Pedagogics at its end returns to its beginning. The first and second divisions already contain the idea of the system necessary for the Present.

§ 12. The idea of Pedagogics in general must distinguish,

(1) The nature of Education in general;

(2) Its form;

(3) Its limits.

§ 13. The nature of Education is determined by the nature of mind—that it can develop whatever it really is only by its own activity. Mind is in itself free; but if it does not actualize this possibility, it is in no true sense free, either for itself or for another. Education is the influencing of man by man, and it has for its end to lead him to actualize himself through his own efforts. The attainment of perfect manhood as the actualization of the Freedom necessary to mind constitutes the nature of Education in general.

—The completely isolated man does not become man. Solitary human beings who have been found in forests, like the wild girl of the forest of Ardennes, sufficiently prove the fact that the truly human qualities in man cannot be developed without reciprocal action with human beings. Caspar Hauser in his subterranean prison is an illustration of what man 10would be by himself. The first cry of the child expresses in its appeals to others this helplessness of spirituality on the side of nature.—

§ 14. Man, therefore, is the only fit subject for education. We often speak, it is true, of the education of plants and animals; but even when we do so, we apply, unconsciously perhaps, other expressions, as „raising“ and „training,“ in order to distinguish these. „Breaking“ consists in producing in an animal, either by pain or pleasure of the senses, an activity of which, it is true, he is capable, but which he never would have developed if left to himself. On the other hand, it is the nature of Education only to assist in the producing of that which the subject would strive most earnestly to develop for himself if he had a clear idea of himself. We speak of raising trees and animals, but not of raising men; and it is only a planter who looks to his slaves only for an increase in their number.

—The education of men is quite often enough, unfortunately, only a „breaking,“ and here and there still may be found examples where one tries to teach mechanically, not through the understanding power of the creative WORD, but through the powerless and fruitless appeal to physical pain.—

§ 15. The idea of Education may be more or less comprehensive. We use it in the widest sense when we speak of the Education of the race, for we understand by this expression the connection which the acts and situations of different nations have to each other, as different steps towards self-conscious freedom. In this the world-spirit is the teacher.

§ 16. In a more restricted sense we mean by Education the shaping of the individual life by the forces of nature, the rhythmical movement of national customs, and the might of destiny in which each one finds limits set to his arbitrary will. These often mould him into a man without his knowledge. For he cannot act in opposition to nature, nor offend the ethical sense of the people among whom he dwells, nor despise the leading of destiny without discovering through experience that before the Nemesis of these substantial elements his subjective power can dash itself only to be shattered. If he perversely and persistently rejects all our admonitions, we leave him, as a last resort, to destiny, whose iron rule must 11educate him, and reveal to him the God whom he has misunderstood.

—It is, of course, sometimes not only possible, but necessary for one, moved by the highest sense of morality, to act in opposition to the laws of nature, to offend the ethical sense of the people that surround him, and to brave the blows of destiny; but such a one is a sublime reformer or martyr, and we are not now speaking of such, but of the perverse, the frivolous, and the conceited.—

§ 17. In the narrowest sense, which however is the usual one, we mean by Education the influence which one mind exerts on another in order to cultivate the latter in some understood and methodical way, either generally or with reference to some special aim. The educator must, therefore, be relatively finished in his own education, and the pupil must possess unlimited confidence in him. If authority be wanting on the one side, or respect and obedience on the other, this ethical basis of development must fail, and it demands in the very highest degree, talent, knowledge, skill, and prudence.

—Education takes on this form only under the culture which has been developed through the influence of city life. Up to that time we have the naïve period of education, which holds to the general powers of nature, of national customs, and of destiny, and which lasts for a long time among the rural populations. But in the city a greater complication of events, an uncertainty of the results of reflection, a working out of individuality, and a need of the possession of many arts and trades, make their appearance and render it impossible for men longer to be ruled by mere custom. The Telemachus of Fenelon was educated to rule himself by means of reflection; the actual Telemachus in the heroic age lived simply according to custom.—

§ 18. The general problem of Education is the development of the theoretical and practical reason in the individual. If we say that to educate one means to fashion him into morality, we do not make our definition sufficiently comprehensive, because we say nothing of intelligence, and thus confound education and ethics. A man is not merely a human being, but as a reasonable being he is a peculiar individual, and different from all others of the race.

§ 19. Education must lead the pupil by an interconnected series of efforts previously foreseen and arranged by the teacher to a definite end; but the particular form which this shall take must be determined by the peculiar character of the pupil’s mind and the situation in which he is found. Hasty and inconsiderate work may accomplish much, but only systematic work can advance and fashion him in conformity with his nature, and the former does not belong to education, for this includes in itself the idea of an end, and that of the technical means for its attainment.

§ 20. But as culture comes to mean more and more, there becomes necessary a division of the business of teaching among different persons, with reference to capabilities and knowledge, because as the arts and sciences are continually increasing in number, one can become learned in any one branch only by devoting himself exclusively to it, and hence becoming one-sided. A difficulty hence arises which is also one for the pupil, of preserving, in spite of this unavoidable one-sidedness, the unity and wholeness which are necessary to humanity.

—The naïve dignity of the happy savage, and the agreeable simplicity of country people, appear to very great advantage when contrasted on this side with the often unlimited narrowness of a special trade, and the endless curtailing of the wholeness of man by the pruning processes of city life. Thus the often abused savage has his hut, his family, his cocoa tree, his weapons, his passions; he fishes, hunts, plays, fights, adorns himself, and enjoys the consciousness that he is the centre of a whole, while a modern citizen is often only an abstract expression of culture.—

§ 21. As it becomes necessary to divide the work of teaching, a difference between general and special schools arises also, from the needs of growing culture. The former present in different compass all the sciences and arts which are included in the term „general education,“ and which were classified by the Greeks under the general name of Encyclopædia. The latter are known as special schools, suited to particular needs or talents.

—As those who live in the country are relatively isolated, it is often necessary, or at least desirable, that one man should 13be trained equally on many different sides. The poor tutor is required not only to instruct in all the sciences, he must also speak French and be able to play the piano.—

§ 22. For any single person, the relation of his actual education to its infinite possibilities can only be approximately determined, and it can be considered as only relatively finished on any one side. Education is impossible to him who is born an idiot, since the want of the power of generalizing and of ideality of conscious personality leaves to such an unfortunate only the possibility of a mechanical training.

—Sägert, the teacher of the deaf mutes in Berlin, has made laudable efforts to educate idiots, but the account as given in his publication, „Cure of Idiots by an Intellectual Method, Berlin, 1846,“ shows that the result obtained was only external; and though we do not desire to be understood as denying or refusing to this class the possession of a mind in potentia, it appears in them to be confined to an embryonic state.—

§ 23. The general form of Education is determined by the nature of the mind, that it really is nothing but what it makes itself to be. The mind is (1) immediate (or potential), but (2) it must estrange itself from itself as it were, so that it may place itself over against itself as a special object of attention; (3) this estrangement is finally removed through a further acquaintance with the object—it feels itself at home in that on which it looks, and returns again enriched to the form of immediateness. That which at first appeared to be another than itself is now seen to be itself. Education cannot create; it can only help to develop to reality the previously existent possibility; it can only help to bring forth to light the hidden life.

§ 24. All culture, whatever may be its special purport, must pass through these two stages—of estrangement, and its removal. Culture must hold fast to the distinction between the subject and the object considered immediately, though it has again to absorb this distinction into itself, in order that the union of the two may be more complete and lasting. The subject recognizes then all the more certainly that what at 14first appeared to it as a foreign existence, belongs to it as its own property, and that it holds it as its own all the more by means of culture.

—Plato, as is known, calls the feeling with which knowledge must begin, wonder; but this can serve as a beginning only, for wonder itself can only express the tension between the subject and the object at their first encounter—a tension which would be impossible if they were not in themselves identical. Children have a longing for the far-off, the strange, and the wonderful, as if they hoped to find in these an explanation of themselves. They want the object to be a genuine object. That to which they are accustomed, which they see around them every day, seems to have no longer any objective energy for them; but an alarm of fire, banditti life, wild animals, gray old ruins, the robin’s songs, and far-off happy islands, &c.—everything high-colored and dazzling—leads them irresistibly on. The necessity of the mind’s making itself foreign to itself is that which makes children prefer to hear of the adventurous journeys of Sinbad than news of their own city or the history of their nation, and in youth this same necessity manifests itself in their desire of travelling.—

§ 25. This activity of the mind in allowing itself to be absorbed, and consciously so, in an object with the purpose of making it his own, or of producing it, is Work. But when the mind gives itself up to its objects as chance may present them or through arbitrariness, careless as to whether they have any result, such activity is Play. Work is laid out for the pupil by his teacher by authority, but in his play he is left to himself.

§ 26. Thus work and play must be sharply distinguished from each other. If one has not respect for work as an important and substantial activity, he not only spoils play for his pupil, for this loses all its charm when deprived of the antithesis of an earnest, set task, but he undermines his respect for real existence. On the other hand, if he does not give him space, time, and opportunity, for play, he prevents the peculiarities of his pupil from developing freely through the exercise of his creative ingenuity. Play sends the pupil back refreshed to his work, since in play he forgets himself 15in his own way, while in work he is required to forget himself in a manner prescribed for him by another.

—Play is of great importance in helping one to discover the true individualities of children, because in play they may betray thoughtlessly their inclinations. This antithesis of work and play runs through the entire life. Children anticipate in their play the earnest work of after life; thus the little girl plays with her doll, and the boy pretends he is a soldier and in battle.—

§ 27. Work should never be treated as if it were play, nor play as if it were work. In general, the arts, the sciences, and productions, stand in this relation to each other: the accumulation of stores of knowledge is the recreation of the mind which is engaged in independent creation, and the practice of arts fills the same office to those whose work is to collect knowledge.

§ 28. Education seeks to transform every particular condition so that it shall no longer seem strange to the mind or in anywise foreign to its own nature. This identity of consciousness, and the special character of anything done or endured by it, we call Habit [habitual conduct or behavior]. It conditions formally all progress; for that which is not yet become habit, but which we perform with design and an exercise of our will, is not yet a part of ourselves.

§ 29. As to Habit, we have to say next that it is at first indifferent as to what it relates. But that which is to be considered as indifferent or neutral cannot be defined in the abstract, but only in the concrete, because anything that is indifferent as to whether it shall act on these particular men, or in this special situation, is capable of another or even of the opposite meaning for another man or men for the same men or in other circumstances. Here, then, appeal must be made to the individual conscience in order to be able from the depths of individuality to separate what we can permit to ourselves from that which we must deny ourselves. The aim of Education must be to arouse in the pupil this spiritual and ethical sensitiveness which does not recognize anything as merely indifferent, but rather knows how to seize in everything, even in the seemingly small, its universal human significance. But in relation to the highest problems he 16must learn that what concerns his own immediate personality is entirely indifferent.